Professional Arabic Translation Services

Halifax provides professional Arabic translation services. Certified Arabic translation, Arabic interpreter, simultaneous or consecutive, online or live – all Arabic language services, to and from all languages.

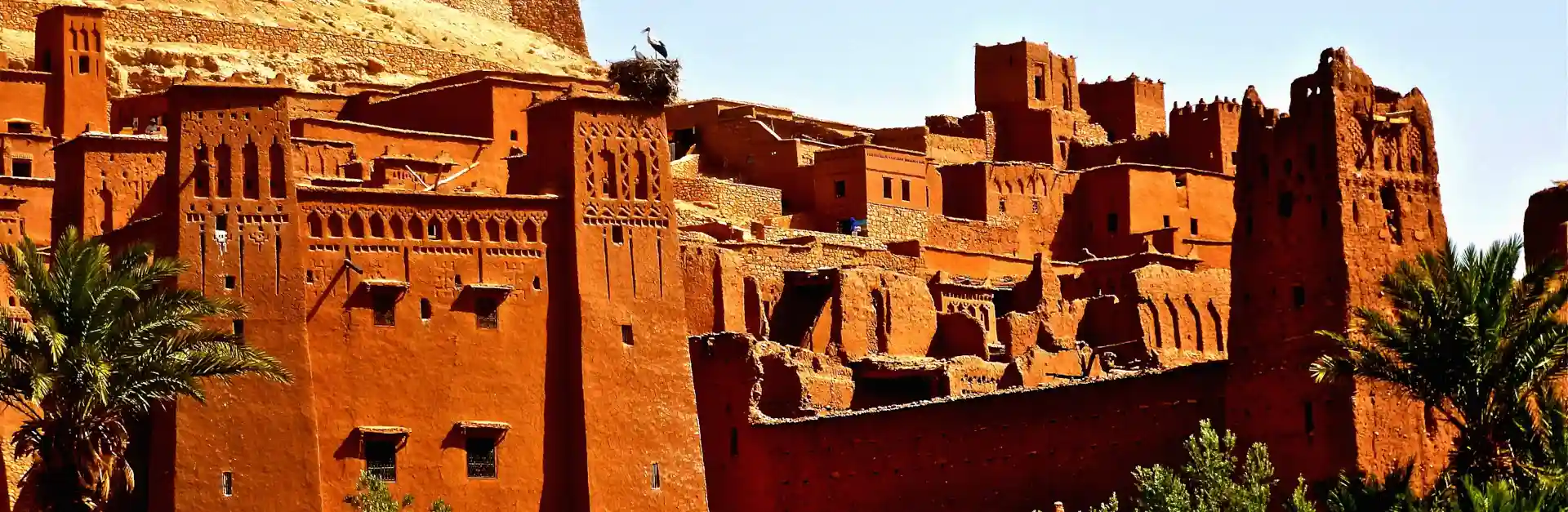

Arabic is spoken in a variety of forms across an immense geographical area, from Iraq in the east to Morocco in the west. While a literary classical Arabic is recognised by all, each country and region has its own version, some of which are difficult or impossible for others to understand. This defines what is called diglossia, where an educated speaker uses two often quite different varieties depending on the context.

The largest population of Arabic speakers in one country is in Egypt (for which reason we have symbolised the language by the Egyptian flag, for want of a better symbol).

Professional translation to and from Arabic

We offer full services including:

- Professional Arabic document translation

- Certified Arabic translation

- Revision, editing or proofreading of Arabic documents

- Arabic document conversion

- Arabic interpreting, online or live

- Video translation & transcription from and to Arabic

Our professional Arabic translation services are the most cost-effective you will find (read about translation rates here).

Arabic translation – a translator’s view

We asked our best Arabic translator to tell us about her language and the difficulties she faces when working with it.

What are the main challenges you face when you work with Arabic?

I grew up in the Arab world, I was educated in Arab schools and worked in Arab countries, so diglossia is not a great problem for me, though it is certainly difficult for most interpreters and others who work with professional Arabic translation. It is very important to develop a feeling for this language, because one word can have many different meanings depending on the context in which it is used. Many words have to be translated descriptively.

Arabic does not tolerate abbreviations. In their writing, Tunisians are increasingly inserting French words written in Arabic: sometimes it is difficult to recognize them if you do not speak French. This has become a common occurrence in other Arab countries as well.

Arabic names and transcriptions are often different from those found in their documents. In Egypt for example, in spoken language, the Arabic letter that should sound like the French j in je is pronounced ‘g’, and you often see the dialect translated into a classical script so that the name Jamil, for example, is pronounced only in Egypt as Gamil, and so is transcribed like this.

Literal translation should be avoided in every way. In Arabic you can find a full page of text without a full stop or a comma, so it takes a lot of effort and time to parse the text and translate it properly.

The Arabic language we translate is the so called Naskh. Vowels, other than long ones, are not written, so you have to recognize the word from its context. This was best expressed by the famous professor Anis Furajh from the American University of Beirut: “We are the only people who must understand in order to read. Everyone else reads to understand!”

My professor, a famous orientalist at the Faculty of Philology in Belgrade, told students that, as the best student in his year, he was proud of his abilities on arrival in Egypt. When he came to Cairo, he asked at the bus ticket counter for a ticket for Alexandria, using a true classical language, which he had mastered perfectly during his studies. The seller replied: “Do you speak English?” He was not educated enough to understand.

It is important for a translator of Arabic to spend time in those countries and gain experience, a good knowledge of Arabic culture and their way of thinking.

What can you tell us about the origins and history of Arabic?

According to the geographical classification of languages, Arabic can now be defined as an Asian-African language whose home regions are the Arabian Peninsula and the Middle East. According to the genetic-linguistic classification, it belongs to the Semitic group of languages. The term “Semitic” is of biblical origin and refers to the book of Genesis, the prophet Noah and his son Sem, who is believed to be the origin of all the Semitic peoples.

The largest language in this group of Semitic languages is Arabic. Arabic is a linguistic group of many dialects originally related only to the Arabian Peninsula.

Traces of Arabic are found in Assyrian sources from the 9th century BC, then in 5th-century BC Nabataean Aramaic inscriptions. Arabic was formed as a separate language in the 5th century BC in the Arabian Peninsula, among the many Arab tribes who lived largely in isolation.

Arabic developed in three stages:

I. Ancient Arabic (5th Century BC – 4th Century AD)

II. Classical Arabic (5th-19th century AD)

III. Modern Arabic (from the 19th century AD).

Ancient Arabic is widely seen in preserved inscriptions in several dialects that belonged to different regions of central and northern pre-Islamic Arabia. Classical Arabic was created in the 5th century and became clearer in the 6th century. The most important moment for this language is certainly the advent of Islam in the 7th century AD and its spread to Asia and Africa. The Arabic language came to its classical form in pre-Islamic poetry, which had a prestigious role in Arabic, and later in the Muslim holy book, the Koran. As the Quranic text was a model of linguistic purity and perfection, the grammatical norm of literary Arabic was created on this basis in the 8th and 9th centuries.

In the late Middle Ages, and especially in the 18th century, the purity of the Arabic language was compromised by the penetration of dialects and foreign elements: Persian and Turkish, above all. But as early as the 19th century, a general revival of the Arab world and the strengthening of Arab nationalism began. In this revival, educational reforms were implemented and printing presses introduced, expanding the number of users of books and newspapers.

In the Arabic-speaking community, from the earliest times to the present, there has been a very pronounced diglossia – a phenomenon in which the speaker community uses two substantially different variants of the same language in parallel, depending on the context. Diglossia is a phenomenon that engages the entire linguistic community, which simultaneously uses the literary/classical language (al-fusha) and the everyday language (al-amiyya), concretised in the form of regional dialects. For Arabs, the native language is that local one, which they learn in the family and immediate environment, while literary/classical Arabic is learned through education and training.

The diglossia emerged as the population was linguistically Arabised over the vast expanse of the Middle and Near East and North Africa in the spiritual and cultural sphere of the new religion. More recently, there have been attempts to overcome the diglossian split as an objective barrier to modernizing, connecting and democratizing the Arab world under the multiple challenges of modernity, through appropriate language and collective mental reform. However, there has been no real success or concrete results. Al-fusha still enjoys undivided prestige among Arabs, even those who have a relatively poor or insufficient command of the classical language – especially them!

Arabic writing

The Arabic script today is one of the most important and widespread kinds of writing in the world (immediately after Latin). It is used in the countries of the Islamic civilization, that is, from Central Asia, through North and Central Africa, and in some periods it reached Europe.

Its origin, development and spread are related first of all to Islam and its spread since the 7th century.

The cradle of Arabic script is the Hijaz and Najd, area in the centre of the Arabian Peninsula, inhabited by a number of Arab tribes.

The creators of the first alphabet were Phoenicians.

The early Arabic alphabet was square and with strict geometric lines, later developing in several directions. The most widespread, cursive form of script, characterized by sparse lines, is Naskh. By all accounts it is quite old (some say it originated in the earliest period of Islam), and is today the dominant official form of script in the press in the Arab world.

The Arabic script has 28 signs for consonants. Vowels began to be recorded only in the late 7th and 8th centuries.

The basic characteristics of Arabic script are:

- recording of consonants and only partially of vowels;

- the letters take many forms, i.e. different positional variants that depend on their place in the word; they are easily identified on the basis of a characteristic central feature;

- right to left direction;

- letter binding;

- some letters bind only to the right;

- little difference between written and printed letters;

- no capitalization;

- avoiding the repetition of identical signs whenever possible; for this reason, a consonant doubling sign was introduced;

- inability to divide words at the end of a row;

- Arabic verbs do not have basic tense forms that would correspond to our past, present and future tense, but the verb occurs in two forms, perfect and imperfect.

and many more features …

The Arabic World

The Arabic world is so broad that it’s difficult to do it justice in a single link. If you would like to know more about it, try Lonely Planet, here are a few links:

Middle East

Lebanon

Egypt

Tunisia

Algeria

Morocco