Professional English translation services

Halifax offers professional English translation in all its forms – We translate English from and to all the world’s most common languages. We also write original English texts. Our prices are among the lowest you will find for a reliable professional English translation service.

English translation

We offer complete language services including:

- Professional English document translation and editing

- Certified English translation

- Revision, editing or proofreading of English documents

- English document conversion

- English interpretation, live or online

- English desktop publishing (DTP)

- Video/audio translation & transcription

Our professional English translation services are the most cost-effective you will find (read about translation rates here).

Why is English so important?

Good English translation shows your company’s professionalism to the widest audience. English is modern lingua franca for many purposes in the world, and the quality of the English language in your document can reflect well or poorly on your business. Good quality English, both precise and expressive, can set you above your competitors, while poor grammar or style can leave a lasting impression of incompetence.

English is used as a mother tongue by people in the United Kingdom, the Republic of Ireland, the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India, South Africa and many other countries. A number of states use it as their official language with their people speaking a patchwork of different tongues. English is currently the fourth most widely spoken mother tongue in the world (after Chinese, Spanish and Hindi), but the dominant presence of English in everyday life and the fact that English holds the title of the favourite foreign language in the world sets a high bar for our standards in English.

What kinds of modern English are there?

Between 1.5 and 2 billion people speak English in one form or another. Although Chinese and Spanish may have more native speakers, English is more widespread and far more common as a second language. It is an official language in 88 sovereign states and territories. Your familiar Microsoft Word lists some 18 varieties of English in its spell-checker, from Australian to Zimbabwean English, but there are many more. Even within England, some people speak dialects that a person raised on ‘BBC English’ can have trouble understanding.

Then there is a vaguely-defined language you could call ‘international English’, used by many non-native speakers. This language tends to correspond to ‘good’ UK English with a restricted vocabulary; it often contains elements of other English varieties and of foreign languages. EU institutions often use their own melange that can sometimes sound strange to a native English speaker, though the European Commission has some excellent guidelines on how to write good English or provide good English translation (e.g. Misused English Terminology in EU Publications, the English Style Guide, the Country Compendium, all EU publications).

British? American? Something else?

That depends on who will read your document and why. For most audiences and purposes in Europe, we recommend standard UK English. US English is common when the document will have an American audience. Other varieties are also possible.

But take care about whose UK English it is. A native speaker is recommended, but not just any native speaker. Many British people speak a colloquial language that is hard for a non-native to understand, even one who speaks excellent English. A good English translation is one where the translator has understood this, and suited the language to the intended audience.

Whichever kind of English you choose for your documents, it should be written consistently, e.g. without inadvertently mixing British and American English.

You should be aware, though, that many of the apparent differences between languages like UK and US English are really issues of choice or style rather than of language variant. Words and expressions have bounced back and forth over the Atlantic and been used in slightly different ways over several centuries. The fact that a word is most often used in the US does not make it un-British. Not even the use of ‘s’ or ‘z’ (e.g. criticize/criticise) is convincingly one or the other, and few native English speakers can tell the difference in many phrases. Is this balderdash (Elizabethan English with Nordic origins), poppycock (Dutch origin), baloney (Italian), malarkey (American-Irish), hogwash (15th century English) or just bunk (US)? Most English natives would be comfortable with all of these. (For an entertaining look at the relations between UK and US English, you can do worse than read The Prodigal Tongue by Lynne Murphy.)

More important is the context in which expressions are used. A hood (from old German) and a bonnet (from French and ultimately Latin) are both US and UK headgear, though one is used exclusively as an engine cover in the US and the other exclusively for the same thing in the UK.

For a good English translation you should just make sure you use a professional English translator. If your text is for public view, like a magazine article or an advert, you should also ensure that it is revised by an English translator who is also a good writer.

What is special about English?

English is a particularly flexible language, its vocabulary is the most varied of any modern European tongue. This allows nuanced writing, but also inaccuracy and obfuscation.

How did this unusual wealth of words come about?

Before the Norman conquest, Britain had been a more or less typical northern European country. Its language had roots in old German, like other Nordic countries. Then two things happened.

In 1066 the Normans invaded and imposed themselves as a ruling class, speaking their own language, French. British society had two distinct layers, each with its own language (the basis of the British obsession with ‘class’ even today, and of their love-hate relationship with the French). The rulers determined administrative affairs, using and developing a French-based vocabulary. Monks, who developed the written word and academic study, used mostly Latin.

Towards the end of the fourteenth century, writers began to use English again for administrative and commercial purposes; but they continued to use French and Latin words because the original English ones had fallen into disuse or had never existed. The language developed in two layers: one with words about everyday life, and a more specialised one for specific purposes. Some of the French words gradually trickled into common usage, but others remained mysterious to ordinary people.

Then, during the Renaissance, many classical texts were translated into English. But unlike in Latin-based languages, ‘native’ English equivalents did not exist for many Greek or Latin words, so many authors simply anglicised the original words. This reinforced the division between everyday and specialised language. Over 80 percent of the most common words we use today still descend from Anglo-Saxon, but for intellectual and artistic purposes, we use almost three times as many terms of French or Latin origin.

What does this mean for modern English and English translation?

This has resulted in a rich language that can be used with great precision, but can also be easy to misuse. A writer who wishes to impress may be attracted to the cultivated sound of Latin-based words and sentence structures. These are often over-used in institutional writing cultures, especially where hierarchy is more important than effective work. They are often used as a cover for dull or lacking content.

Words of Latin origin are often used in professional jargon. Such specialised language is needed for experts to communicate precisely, but in some fields it has developed together with this tendency to confuse the reader. As a result, many people wrongly imagine that a text needs to be opaque to be professionally correct. This is often the case, for example, in legal language, which can be quite unnecessarily turgid.

Here is a simple believe-it-or-not example of readability taken from an HSE report (Health, Safety, Environment), using roughly similar words of different origin that illustrate different ways of writing: e.g. ‘way’ (from old German) or ‘methodology’ (from Latin and Greek). One is rich in noun forms and uses the passive voice, the second replaces these with active verbs.

“The need for further research into response process optimisation was obviated by their knowledge of the appropriate technical analytical methodology, permitting greater rapidity in response times should there occur events unharmonised with foreseen developments.”

And re-phrased a bit:

“Since they already knew the best way to understand what was happening, they could respond faster if plans went wrong.”

No prizes for guessing which is more readable. In the first, you struggle to find who was doing what. The use of words and structures that can sometimes be justified does not make the first example more informative or professional. But we are all tempted to show our ability to use more complex forms.

As for English translation, many translators were trained in an academic environment where ‘clever’ use of language was encouraged. It can take a while to shed such habits and produce readable prose.

This historic complexity, then, makes English a language of opportunity. But it can also be a lexical quicksand that draws us into using it inappropriately and missing the main point.

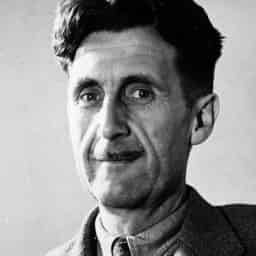

The English writer George Orwell summed it up like this in his classic essay Politics and the English Language, in 1946:

- Never use a metaphor, simile or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

- Never use a long word where a short one will do.

- If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

- Never use the passive where you can use the active.

- Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

- Break any of these rules sooner than say anything barbarous.

See also: What else can affect the quality of a translation?

You may also be interested in:

The Oxford Guide to Plain English, Martin Cutts, 2013, Oxford University Press ISBN10 0199669171, ISBN13 9780199669172

Plain English, Chris Mitchell

Creative English writing

Halifax offers excellent English copywriting services. Make sure your web pages or other texts are well written in an appropriate style. Call or mail us for an offer.

How should I translate a web site into English?

To translate a web site to English is like translating it into any other European language, except that the number and diversity of readers is likely to be considerably greater. Few others than Poles will read a Polish web site, but so much internet content is in English that you may expect readers from all over the world. Many will not speak English as their first language.

English translation is therefore a special case that should be approached with greater care. You must be sure your translator is both analytical and creative, knows the English language and its variants well, is skilled at expressing concepts briefly, and can ask you the right questions.