Last week I was editing a translated text about road traffic safety.

At the weekend, I drove out of Belgrade down a busy country road, and the text I had been working on made me notice something I hadn’t before. I’ve driven this way hundreds of times, but suddenly it reminded me of a road in northern Jutland. How could it do that? The rolling hills contrast starkly with the low-lying Skagen sandscape, the boisterous vegetation quite different to the coarse grass and wild roses that bind the sand dunes of the Skagerrak littoral.

What was it?

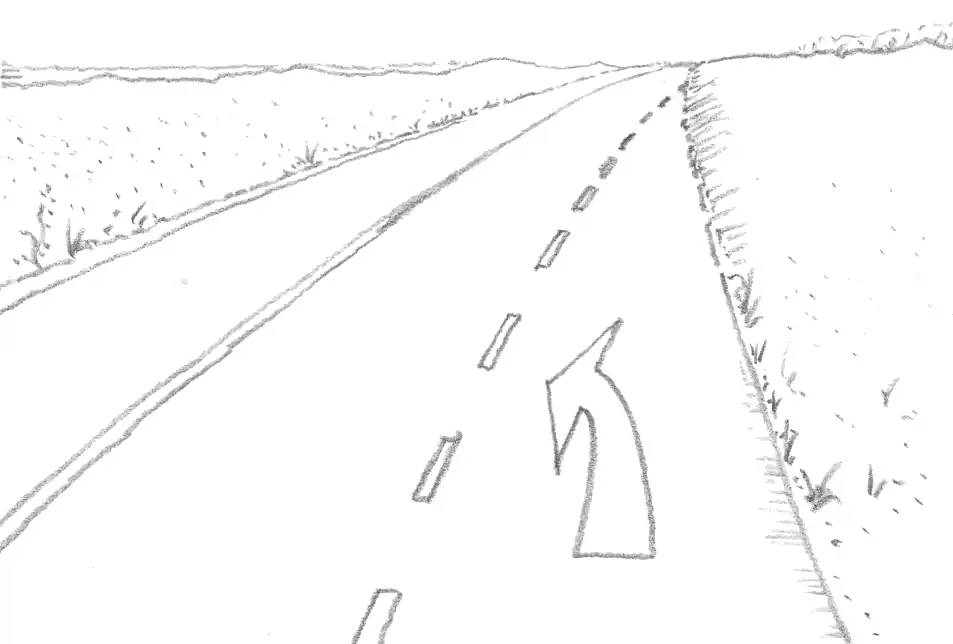

That was it, it was not a similarity but a contrast. One of the two lanes in my direction came to an end, and it was the right-hand lane that terminated.

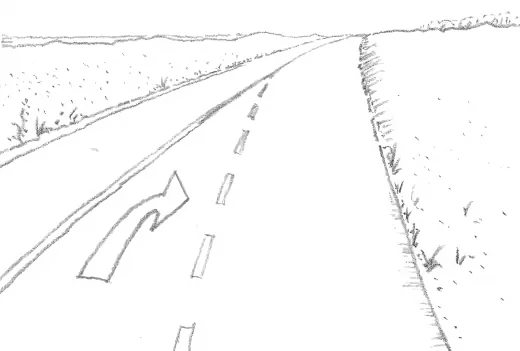

Here’s how I remembered the Danish road.

This makes a lot more sense to me, it puts the principal responsibility where it belongs. But then I am not Serbian.

Think about it. You are driving along as you should in the right-hand lane, and a vehicle passes you. The road markings tell you that you must give way to the overtaking vehicle as the lanes merge. The onus is not on the overtaker to ensure a safe manoeuvre, but on the overtaken. This seemed all wrong.

In his 1991 book Cultures and Organizations*, the sociologist Geert Hofstede used data from a similar set of IBM employees in some 50-odd countries to examine cultural differences between countries. He identified five dimensions of culture, and due to the similarity of his samples he could rank each country. The first dimension he called ‘power distance’ (PDI), it describes how a culture handles inequality, and refers to ‘the emotional distance between subordinates and their bosses’.

He defined power distance as the extent to which the less powerful members of institutions within a country expect and accept that power is distributed unequally.

In a low-PDI country: “The use of power should be legitimate and subject to criteria of good and evil; Skills, wealth, power and status need not go together; All should have equal rights; Powerful people try to look less powerful than they are; Small income differentials in society, further reduced by the tax system”.

In a high-PDI country, “Might prevails over right: whoever holds the power is right and good; Skills, wealth, power and status go together; The powerful have privileges; Powerful people try to look as impressive as possible; Large income differentials”.

Hofstede ranked each country on a scale between zero and 100. The lowest (surprisingly for me) was Austria scoring 11, the highest Malaysia at 104 (yes). Northern Europe, especially the Nordics, scored low, the Middle East and the Far East scored high. Countries with authoritarian regimes scored notably higher than genuine democracies, the USA at 40 points was a lowish-medium.

He found clear correlations between PDI and geographical latitude, population size and wealth. Low PDI correlated with less traditional agriculture, more modern technology, more urban living, more social mobility, better education and a larger middle class. Interestingly, higher PDI went with a country having been part of the Roman empire or being colonized by such a country, one example of how cultural differences persist over long time spans.

Denmark came 3rd lowest at 18 points. Yugoslavia (as it then was) scored 76, just under West Africa and India at 77.

I was reminded of a Serbian friend of mine. After we had been in Copenhagen together he said: “These guys drive Fiat Puntos”. In Belgrade, anyone aspiring to status has a BMW or Mercedes, even Audi seems a bit infra dig these days. The car, of course, is the ultimate flauntable power status symbol.

You can see how all this relates to the road markings: the overtaker is more powerful, you have to give way to him, and this is natural in one culture, not in the other. Roads are often re-surfaced, potholed pavements almost never.

I remembered all the articles I’d seen in Serbian newspapers with titles like: “The 100 most powerful CEOs in Europe” or “The 50 most powerful women in sport”. Power is a preoccupation. I suspect Danish papers would be more likely to run “the 50 most popular sportspeople”.

Hofstede”s work is from the 1970s-90s, but culture changes with glacial speed, extending through generations and even millennia. I should not have been surprised by the difference I noticed on the road: culturally, everything is relative. Neither culture can be said to be better or worse, they are just historically different.

But… what happens in practice on that road is that slower vehicles pull out into the left-hand lane well in advance of the merge, so they are not forced to brake. Then some of the faster drivers overtake them on the inside, not quite the safest practice. Perhaps there are non-relative outcomes after all.

Fasten your seat belt, culture has consequences.

*Cultures and Organizations – Software of the mind, Geert Hofstede 1991, McGraw-Hill

#road traffic safety #editing #translation #power #roman empire