When you deal with data, recognize the risks

For a translation agency, the GDPR is an important law. In our efforts to comply with it, we keep personal data only on a legitimate basis such as the data owner’s consent, and only as long as we need it. We also do our best to ensure that our suppliers (for the most part translators and interpreters) also take care of it.

Our clients send us all kinds of documents for translation. Most of them are commercial texts that would hardly cause trouble if leaked, but some contain personal data that could be used for identity theft, or IP that may be a business secret.

On paper

We print some documents on paper, usually when they need to be stamped by a court-authorized translator. Often, the client wants the stamped document scanning and sending by mail, so we are left with the prints to be disposed of. As we try to be environmentally friendly, some of them are used as scrap paper which is finally binned, but we can never be sure what happens when the municipal waste truck comes by to empty the container. Rubbish can be spilt, papers can blow on the breeze.

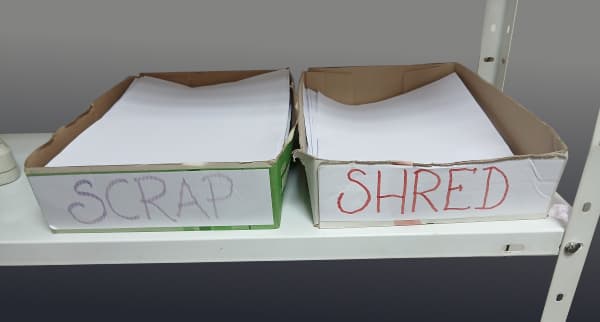

The guidelines for project managers are therefore clear: if the client would not mind this page being found on the street, pop it in the scrap paper box. If they would, shred it.

In bytes

What is simple in the real world can be surprisingly complicated in the virtual. Of course, we take all the precautions: contracts have careful confidentiality clauses; encrypted mail runs on our own mail server; freelance translators work on our translation management system that runs and is stored on our own server; use of Google Translate, even as a supporting tool, is forbidden.

One point, however, is often missed by a casual observer. What happens when a translator needs to research a topic? Your average user will still open Chrome (or Edge or Safari) and make a search.

But Chrome is not just a browser. Chrome is a data-scraping instrument that shamelessly records every scrap of information that flies by its nose. On the phone, for example, it tracks and reports your location even if you have this feature turned off. It is ruthless. Whatever you put into Google will be used to train large language models – AI. And once it goes in, nobody, not even the AI developers themselves, can tell where and when it will come out, or in what form. It may also be sold on to data broker companies that can piece it together with other information on the web to identify you and build a precise picture of your habits, interests, work, friends, location and vulnerabilities: the kind of data that is regularly hacked and sold to malicious actors on the dark web. Chrome’s competitors do the same. Check out this link to see what happens in a simple Bing search (and read the comments). As for AI tools like ChatGPT, any sensible person familiar with the English proverb will take a particularly long spoon.

What can we do?

In the digital world, we need the same logic as shred-or-scrap. Never, ever, put in a phrase that you would not want to find blowing down the street.

Of course, the safest is just never to use the ‘free’ tools provided by outsized tech corporations. There are excellent alternatives. Our recommendation is to use the Brave browser or you can use Firefox and search with Duck-Duck-Go. And if you really must use Windows, turn off the automatic use of Co-pilot.

Remember the paper boxes, and be aware that the internet is a lot less secure than the municipal garbage truck.