No 18 in a series about translating from Serbian (and other languages) into English

Why do we use capital letters?

The other day I was confronted with this translation: “The Ministry has strongly supported the Project, although the Contract has not yet been signed.“

Now, German starts every noun with a capital letter, but English doesn’t. I don’t pretend to be an expert on what Serbian is supposed to do, but it seems somewhere in between, and rather randomly at that. And this apparent capriciousness often jumps the language barrier: time and again I see translations from Serbian that seem to use capitals to confer a special importance on the example of the noun they are mentioning. This habit suggests that when writing about a specific ministry, project or contract, the word should be capitalized to indicate that it’s this one we are talking about.

Capital letters in legal texts

In contracts or other legal texts (see also this article), initial capital letters can be used to define a specific example of something. This is often done in a preamble, where you might find: “This contract (hereinafter ‘the Contract’), is signed by…” or “The parties to this Contract (hereinafter ‘the Parties’) agree to…”. So if the term has thus been defined with a capital letter, you may use it with that specific meaning in the rest of the document. But if you do use a capitalised term like this, make sure you have first defined it. We see all kinds of capitalised nouns used as if they have been so defined. If they haven’t, don’t.

What is standard in legal texts is not always desirable in other types of document. This particular usage is formal, and generally limited to texts in which the author wants to be completely certain that nothing can be misinterpreted, but has scant regard for style.

The same goes for a number of words conceived for use in legal documents. The ‘abovementioned or aforementioned items’ is often seen. It’s an accurate translation of a common Serbian phrase, but that doesn’t make it a good one in English. Outside a specialised text it sounds pedantic. ‘These items’ is usually just as accurate and more natural. The same goes for hereinafter, notwithstanding, insofar as, pursuant to, etc. But I digress.

In names

Of course, a capital letter is usually used to indicate a proper noun, someone’s or something’s name: David; The Prince of Darkness; Ljubljana City Council; Jack the Ripper, The Republic of North Macedonia, Islamic State, The Mississippi. It is not used for generic ones: me, a prince, a city council, each ministry, a river, states in the Middle East or in the middle of nowhere.

Titles use upper case first letters in English, at least for all the important words (not for articles, conjunctions, and prepositions): The Name of the Rose; The Law on Changes to the Law on Public Procurement; An Introduction to Mathematical Analysis; The Duke of York; The Sexual Offences Act 2003; For Whom the Bell Tolls.

So, for example: ‘The Law on Local Self-Government has been changed, following an analysis of several other countries’ laws on local government’; ‘The government (or, if you really must, ʻthe Governmentʼ, as a form of shortened title) is considering a new law on the prohibition of bad translation’ (this is a description, not a title). The new law (not ʻLawʼ) will be entitled ‘The Law on the Suppression of Bad Translation’.

Serbian is different from English. It capitalises only the first word. This can mean that it is sometimes unclear where the title ends and the sentence continues, especially when Serbian titles can be surprisingly lengthy. If the title is very long, it is sometimes better to break the rule and capitalise only the first letter in English too, as it can look a bit silly when a whole paragraph is dotted with uppercase letters.

The use of initial capitals in English is quite enough to indicate a proper noun or title. One thing you should not do is to indicate a proper noun phrase with quotation marks. „These things“ are peppered everywhere in Serbian, and often seem to be used on almost all proper nouns. In English they are used to mark speech or to emphasize the tentative or quoted use of a phrase.

Both single and double ones are used in English. In American English the double ones seem to be preferred, while Brits use single ones rather more. You can use both when you need to nest them: He dropped a brick on his foot and said “ouch!” Later, he told me: “I said ‘ouch!’ ”

But not to indicate a proper noun or noun phrase:

„Službeni glasnik Republike Srbije” = Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia.

„HALIFAX d.o.o.“ = Halifax d.o.o.

Serbian companies often like their names all in capitals for some reason that escapes me. Please not in English unless you are following a deliberate graphic brand standard.

A capital letter is used to start a sentence; not usually after a colon or semicolon. One exception is when it starts a quote. She called out: “Is there anybody in there?” Another is if you are American: US English often uses a capital letter here.

Geography

And then there are places. Use capitals for well-defined territorial units or concepts, things you can think of as having names. Germany is a country, a state; West Germany was a country but it no longer exists, the same area is now western Germany. Territories like eastern and western Europe are vaguely defined, so the expression ‘eastern Europe’ is a description, not a name.

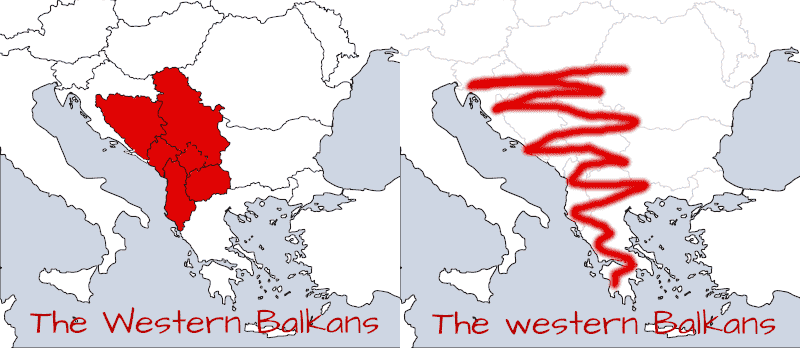

An expression like ‘the Western Balkans’ is today used to mean Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Albania, North Macedonia, Serbia and Kosovo (whether or not you regard the latter as a part of Serbia). Before Croatia joined the EU, that country was also a member, but no longer is, however westerly it lies in the Balkan peninsula. This is a concept, a political one. The common point of these countries is not their location, but their expressed and currently frustrated desire to join the EU. If you wrote it without a capital letter, ‘the western Balkans’, it would include Croatia, and parts of Slovenia and Greece.

The same may be said of a concept like ‘the West’. This includes states all round the globe, both to the east and the west of wherever you are standing. It is usually used to mean ‘rich countries that espouse democracy and a market economy’: precious little to do with geography.

Finally, why do we call capital letters ‘uppercase’? When printing presses were set up with individual lead character elements, the capital letter type was often kept in a wooden case that stood above the one containing the others, in the upper case. How language evolves.

#translatingintoenglish #translationintoenglish #Translation #Translator #Translationagency #Translationservices #HalifaxTranslation #Prevod #Prevodi #Prevođenje #Prevodjenje #Prevodilac #PrevodilackaAgencija #PrevodilackeUsluge #PrevodilačkaAgencija #PrevodilačkeUsluge #capitalletters #capitals #uppercase

In English?

As a proper noun in an English text, I would capitalise it, and not just the first word like in Serbian: Matica Srpska. No?

Hi!

What about Matica srpska? Should s be capitalized or…?